A month of sharing and spirituality, Ramadan is an opportunity for Algerian households to indulge in many traditions. Among these, the Bouqala game occupies a privileged place among the women of the cities of Algiers, Blida, Cherchell, Tlemcen or Constantine and Ghardaïa.

The term ”Bouqala“ or ”Aliwane” in Mozabite first refers to a clay vase, but also to short poems, sometimes improvised, recited by women gathered in the terraces of the Kasbahs or in the patios, after dark. During this game which mobilizes an earthen vase (Bouqala), handles and natural perfumes, a fumigation with a Kanun is carried out to ward off evil spirits and purify the vase. The latter is then filled with water and covered with a scarf while an invocation is recited.

The game can begin: the participants place personal silver items such as rings or bracelets in the vase. They tie a piece of cloth thinking about a loved one while a poem is recited, then an object is drawn from the vase. The owner of the object is the recipient of the omen contained in the short poem, often evoking the themes of love, death, separation or unfulfilled desires. During several rounds, the Bouaqal (plural of Bouqala) can indeed be porters of good or bad omens and are interpreted by the participants.

“The ritual of the bouqala is a traditional game of divination. Women gather around an officiant, often an old woman, and each one places a jewel in an earthen vessel. The officiant recites a poem, and then a young girl randomly takes one of the jewels. The one to whom it belongs must find in the recited poem what can illuminate her life, her loves, announce her departures, joys or misfortunes. ” – Excerpt from the book La Bouqala by Mohamed Kacimi and Rachid Koraichi

Photo: iñaki do Campo Gan – Bouqala with the artist Souad Douibi

A poetic and oral tradition, the Bouqala is however not just a pastime that would punctuate the nights of Ramadan. It represents an “urban social fact” where women have the opportunity to show poetic creativity. It is also a heritage, mobilizing the derija, which was used in particular to convey messages of resistance during colonization. According to political scientist Karima Ramdani, divinatory rituals would then serve women to “take back control of their destiny, to free the future from what today disfigures it”.

He came to me with his green hand and offered me a hundred pearls.

Bad times took hold of him, he betrayed me by leaving me barren.

But thank God, the Motherland appealed to him: he went to seek freedom.

He came to me with his green hand. He appeared to me in a dream.

He laid on my mourning clothes, roses and jasmine.

Since oral traditions were generally depreciated by the colonial authorities, the dialect expression of the Bouqala was often perceived during this period as inferior to works written in literary Arabic. In this context, its subversive character has often been ignored in the writings on this game and in general on Algerian oral cultures. Some, like the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu or the doctor and writer Laadi Flici, however, see in this improvised poetry drawing on dialect, a transformative scope.

Thus, during the 1950s, many poems recited during the Bouqala game explored the themes of freedom or the absence of a loved one who had gone to the front. The game is marked by the history of the country, since the personal, political and social spheres were inseparable at that time.

In the aftermath of independence, interest in the Bouqala did not wane. State programs – including those produced by the writer and columnist Kaddour M’hamsadji – give it a national echo and invite the audience to share poems while consolidating its status as poetry belonging to the popular heritage of the country. Although the practice of the Bouqala is no longer based on its divinatory aspect, the game is today one of the symbols of the country’s female oral poetry. During this holy month, the Bouqala constitutes a cultural wealth to be revisited and safeguarded for the next generations.

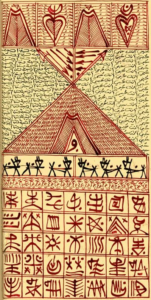

Illustration: Rachid Koraichi – The Bouqala

Translated by hope from : The Casbah Post