Algeria’s litany of invaders have shaped a land where echoes of history’s greatest empires still catch in the desert winds; but visitors today will also discover a country finding its own voice

At the museum in Djémila I spied a sublime sight. It was a Roman mosaic depicting the licentiousness of the god Bacchus: murder, sacrifice, orgy and wine. It was quite the show. It also caused me to ponder something that, up until then, I hadn’t thought about: how might modern Algeria be represented in tesserae? After some deliberation I decided that, regardless of what was depicted, it would be an utterly mercurial sight. After all, so little is known about Africa’s largest country.

The Djémila Museum lies within the ruins of the old town and is filled with mosaics

I started conjuring the Algeria mosaic in my head, piecing together bits of classical civilisations, oases bearing the sweetest dates, Mediterranean sunshine and scorching sands migrating wispily across Saharan dunes like transient djinns. It would be a bit frayed at the edges, representing the turbulent decades that saw this North African behemoth firmly off travellers’ itineraries. But Algeria has changed in recent years. With security vastly improved, its mosaic of historical and cultural wonders is once again reachable – and barely a three-hour flight from London. It is something that a new vanguard of visitors will be eager to explore, even if procuring a visa is tricky, thanks to the Socialist siege mentality of the ruling regime making it tough for those not travelling as part of an organised tour.

“Algerians are a mixture of many peoples,” said M’hamed Gueraini, a gentle giant of a guide, upon meeting our small group at Algiers airport. “We’re more Berber and Arabic than French, Roman or Ottoman, but overall, we’re unique.”

The Martyrs’ Memorial towers over the city, reminding its citizens of the million lives that were given in the battle for independence from the French in the 1950s and early ’60s

That cultural mix quickly materialised on the drive into capital Algiers. M’hamed delivered a potted summary of 3,000 years of history as the city’s denim-blue Mediterranean coastline drew near, beginning his tale in 800 BC. This was when the Phoenicians were trading with Carthage (Tunisia), he said, before Rome conquered all. In turn, the Romans were swept aside by Berber-Arab dynasties, who ushered in Islam. He scarcely need mention later occupations: downtown Algiers revealed lustrous domes dating back to Ottoman rule, while the French colonisation of 1830 was apparent in housing blocks of Neoclassical finery.

Algiers is a city of hills and café culture. Every morning, I walked from my hotel in Telemly district to grab a black coffee and a croissant, conjuring memories of Marseilles: the déshabillé architecture, the horn-blaring traffic and the busy seafront marinas all felt oddly familiar. Yet Algiers’ apogee is found in Martyrs’ Square and its kasbah. Here the Mediterranean sunshine cast shadows from the surrounding minarets and Art Deco architecture onto the city’s main plaza, which was lively in the bustle around the Friday prayer. Families browsed stalls of hanging Deglet-nour dates, Berber costumes and tagine dishes as their children excitedly chased pigeons. But it wasn’t always like this.

Life in Algiers kasbah

“In 1832, the French massacred nearly 4,000 people who were defending the kasbah’s Ketchaoua mosque from being converted into a cathedral,” said M’hamed. In his words I could almost hear the gunfire entering the kasbah, as if the higgledy-piggledy narrow lanes trapped an inescapable palimpsest of history within its labyrinth.

The kasbah was once called Icosium, a Phoenician port that acquired its current guise as a walled medina around the mid-10th century AD, under the founder of the Berber Zirid dynasty which went on to rule parts of the North African Maghreb. Elsewhere, I had seen medinas so gentrified that they had lost all connection with the past; but here, the surviving mashrabiya (screen balconies) and cramped workshops of woodworkers and brass metalworkers nurtured authenticity in lanes politically charged with murals, such as that of Emir Abdelkader, an Islamic scholar and military leader who unsuccessfully resisted French occupation and died in exile in 1883 in Damascus.

A mural of Emir Abdelkader, a religious scholar and military leader who led the struggle against the French invasion of Algeria and has become a powerful symbol of resistance even today

Secreted within the kasbah were several sumptuous palaces from the era of Ottoman rule (1516-1830), during which Algiers grew rich from trade and piracy along the Barbary Coast. The 1799 palace of the Ottoman governor bore a sumptuous courtyard of marble fountains encircled by columns that supported horseshoe-shaped arches. Its hammam was now a themed restaurant, and over a meal of couscous, grilled vegetables and lamb, M’hamed filled in the blanks. He explained that after France superseded the Ottomans it took over a century for Algerians to revolt against their rulers, with conflict finally erupting in 1954. Independence came eight years later, but at great cost: “One million Algerians died during the revolution,” he finished.

Independence unleashed chaotic decades of authoritarian rule, a coup d’état and a vicious civil war against Islamic extremism. “But things are changing,” said M’hamed. “The government has been listening to recent peaceful protests for more rights. We call it the ‘Revolution of Smiles’.”

“The irony of the erotically charged House of Bacchus mosaic existing in a devout religious society wasn’t lost“

Roman excesses

Smiles aplenty I would discover over the next ten days as we travelled Algeria’s hinterlands. I was touched by the delight expressed by locals thrilled that I’d taken the time to visit their country. One man in a flowing ankle-length thobe insisted on paying for the tea that I bought as the seller poured it from a large brass teapot.

“Algeria is your second home,” he smiled.

A tea seller clutches his bronze kettle

The Romans felt at home here too. The following day we ventured 350km eastwards to visit Djémila, venturing into the ancient Berber kingdom of Numidia, the eastern part of which was annexed by Rome in 46 BC. The drive climbed into the mountainous Bibans, or ‘Iron Gates’, as the French called them, and onto a plateau of chocolate-brown arable land where olive trees grew in abundance.

Algeria is awash with Roman ruins. Djémila, or Cuical, was founded in around 96 AD on a hillside (900m above sea level) in the reign Emperor Nerva. It was created for demobilised Roman legionnaires to settle down in after they had conquered the area. “Built on the border with Mauretania Caesariensis, trade made the city rich,” said M’hamed. “It’s the finest Roman site in North Africa.”

Ancient Roman paths in Djemila

Djémila’s flagrant opulence was impressive. Its small museum was wall-to-wall with mosaics from the city’s hedonist pagans, while the more pious inscriptions made later by Christian Romans confirmed the former did indeed have more fun. Mosaic scenes depicted Venus seated on a seashell, examining herself in a mirror, and Europa being seduced by Jupiter. The irony of the erotically charged House of Bacchus mosaic existing in a devout religious society wasn’t lost as I gazed at its centrepiece: the slaying of Ambrosia during her transformation into a grapevine.

Dtatues recovered from Djémila are displayed in the museum

Outside the museum, beyond the marble head of Rome’s first North Africa-born emperor, Septimius Severus (ruled 193-211 AD), Djémila appeared like a stone forest in the process of being felled: a chaotic jumble of standing, fallen and truncated columns. The buffeting hot winds reminded me of one of my favourite writers, Algeria-born Albert Camus, who visited Djémila in 1836 and wrote: ‘Without cease, [the wind] whistled powerfully through the ruins, bathed the heaps of pitted blocks, surrounded each column with its breath, and came to spill out in unceasing moans over the forum that lay open to the sky.’

The Severian Temple is named after the Roman Empire’s first North Africa-born emperor

The 4th-century Christian quarter yielded a large basilica near a theatre that was built around 161 AD and was capable of entertaining a third of Djémila’s 10,000 citizens. What did they watch, I wondered? Probably not Christians being fed to the lions. It was in the older pagan quarter, however, where I became a card-carrying time traveller. Throngs of shoppers and traders bustled around my imagination, thronging the paved cardo maximus (main street), which was flanked by arched colonnades once home to shops selling the grain, wine and olive oil that made Djémila so prosperous. As I wandered, sandy-coloured lizards darted among the sun-baked masonry, and near the forum where orators had their say, I spotted a sacrificial altar whose exquisite bas-reliefs depicted a pig, a bull and a ram – offerings to the gods.

Djémila’s crowning glory was laid down during the family dynasty of Emperor Severus, who would eventually die in York, England. The Severian Temple was as sumptuous as any in the Roman archaeological sphere. A couple of buskers strummed hypnotic oud music as I entered the temple via stone stairs that led into an inner sanctum of standing columns with ornate capitals. I tried imagining the rituals eulogising Severus’ power that must have taken place there. From a raised plinth I could see the triumphal arch of his son, the bloodthirsty Caracalla, who killed his brother to usurp power and built this temple to honour his father. History isn’t always as decorous as the monuments that it leaves behind.

Into the dunes

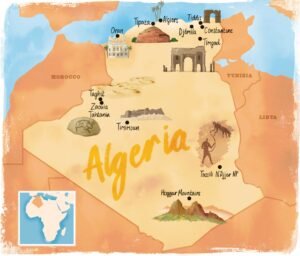

From Constantine we flew two hours south to the oasis of Timimoun, deep within the Sahara desert that covers over 80% of Algeria. The Grand Erg Occidental is the country’s second largest dune system, located on its eastern border with Morocco. This is the realm of the Berber, or Amazigh – the name ‘Berber’ actually derives from a Greek word meaning ‘barbarian’. Throughout Algeria’s history, successive Berber dynasties rose to conquer the land before being vanquished themselves.

“It’s our paradise, but to outsiders it’s like the fire,” said Houari, our local driver-guide, his face enclosed by a white shesh (headscarf). He showed pride at his Berber heritage. “The dialect we speak is Zenata; it’s very old, although the youngsters do not know it, so we speak Arabic on the street.”

He collected me from Hotel Gourara in Timimoun, the terrace of which is the place to be at sunset, clutching a cold Algerian beer and watching the palmery (palm grove) briefly flicker an intense green before the chilly Saharan darkness blots out everything. Timimoun itself is ramshackle, its walled lanes collapsing in on themselves, and the soft sand pathways make for tiring walking. But it also instils an inescapable respect for a culture that thrives in temperatures capable of reaching 50ºC.

One of the many crumbling castles surrounding Timimoun that are being slowly devoured by the wind and san

Heat is good for longevity, insisted Houari. “How old do you think I am?” he asked. I hate these age-guessing games. “Thirty-five,” I responded, diplomatically. “No, 45. The Sahara has given me ten extra years,” he laughed.

Everything else we saw while exploring the ancient ksour (castles) that day was crumbling and old. We drove deeper south, passing Berber women who appeared like ghosts in full-length white haik, their dresses rippling in the winds. We saw tiny gardens amid the sand; each was shaded by date palms and filled with lemon trees, potatoes, carrots and pears. They were fed by one of the world’s largest underground aquifers, I was told: the Bassin du Sahara Septennial.

“But the water is going down,” Houari noted. “The rains traditionally come in spring but are not as heavy these days.”

A mother and her child stroll under the baking sun of Timimoun

Water shortages may have been behind the abandonment of the castle we saw in Guentour, its adobe walls perched on a rock pedestal pitted by wind erosion and engulfed by sand. M’hamed estimated it could be as old as 700 years. “They were used as protection against enemies who came to steal land or supplies,” he said. “Many invaders arrived: the Persians, the Fatimids, the Almoravids and many more.”

One ancient institution had survived allcomers in

Guentour: the zawiya. I removed my shoes and entered the cool interior of a long, arched, whitewashed building bedecked with carpets where platters of buttery dates were offered by way of greeting. Seated before me was the marabout, or sheikh, an elderly religious leader with a pale beard the colour of his robes. He explained that the building dated from the 1500s, but that it still functioned as a madrassa (school) for religious education and a place to mediate local disputes.

Dates growing on a palm

Ah yes, disputes. Time to raise the topic of dates. I had learned quickly in Algeria how to play devil’s advocate, but it didn’t stop me making the mistake of asking what the best Algerian date was. Cue the inevitable fervid discussion. Varieties were bandied about: one had no stone, others could be eaten after months of being buried underground.

“We have 300 types sweetened by oasis water,” explained the sheikh. “We still trade them with communities south of here, such as the Sudanese – sometimes for camels.” Eventually, everyone agreed that the Deglet-nour variety was the sweetest of them all.

I returned later to Timimoun by following a sun-burnished escarpment topped by a weathered ksour from the 11th century. In the grip of sun-frazzled lightheadedness, I could almost picture the defenders who had spent countless soporific days on sentry duty staring south, watching for any new invaders sweeping their way.

The old world

The next day, after venturing 515km westwards, our group entered one of the Sahara’s highest dune fields. A rolling sea of sand surrounded the day’s destination, Taghit, a pretty town of flat-roofed adobe buildings pinched between an escarpment and the erg.

Stiff-legged from the drive, I hurried barefoot up the highest dune, immediately regretting abandoning my flipflops because the silken sand was still scorched from the day’s heat. With every step I climbed higher, rising above my overnight hotel and feeling the soft sand give way as I neared the summit. But it was worth every laboured step. A warm wind carried the voices of children playing football, splicing them with a braying donkey’s complaint. The call to prayer reminded me it was time to head down.

The view from Taghit dune after the exhausting climb to its summit

I would soon fly back to Algeria’s Mediterranean coast to spend two nights in Oran before returning via the coastal railway to Algiers. This penultimate stop would introduce yet another foreign player to the litany of interlopers who shaped Algeria: the Spanish. They left an impregnable hilltop castle in Oran called Santa Cruz, which perches giddily above the circling sea mists. Spain’s limited dalliance with Algeria began with the capturing of Oran in 1509; they wouldn’t surrender it to the Turks for another 200 years.

Before leaving Taghit, however, I got to peer beyond Algeria’s colonial history, glimpsing something far more ancient as we made our way 18km south of the city to Zaouia Tahtania. Here, etched on fractured sugar-lump boulders were exquisitely simplistic petroglyphs of animals from Neolithic times, said to be over 5,000 years old. I delighted myself by working my way through the rocky field. There was none of the sophistication of Djémila’s stellar mosaics, but they spoke just as powerfully of different times and lands. The gazelle bore exaggerated horns, hyena chased ostrich, and a lion appeared so comically square that it could almost be a precursor to Cubism.

“Nobody knows who these people were, but they lived on a more fertile land that has long been lost to the desert,” suggested M’hamed. The allegory wasn’t lost on me. Algeria, a fusion of rich, multitudinous pasts, has emerged from its long spell in the wilderness and is now being rediscovered by an altogether more benign invader: travellers to this mosaic masterpiece of the Maghreb.

1. Timgad

The ruins of Roman Timgad, or Marciana Trajana, were home to some 15,000 people at their zenith, which was between the 1st and 5th centuries AD.

2. Tassili N’Ajjer National Park

In south-east Algeria lies a wild part of the Sahara that is filled with sculpted rocks and pinnacles amid reddish sands. Worth a trip to see the rock art.

3. Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania

This mausoleum, near Tipaza, is shaped like a bronzed cupcake and dates back to 3 BC. It is thought to have been the tomb of Numidian king Juba II and his queen, Cleopatra Selene.

4. Tipaza

Another Roman treasure. This large coastal city, west of Algiers, was a Punic trading post that was conquered by Rome and later fortified by Emperor Claudius.

5. Jardin d’Essais

A beautifully maintained botanical garden in Algiers that was established in the early days of French colonial rule.

6. Hoggar Mountains

A grand mountain range in the Sahara that encompasses Mount Tahat (2,908m), Algeria’s highest peak, as well as the oasis city of Tamanrasset.

7. Tiddis

This beautiful hilltop Roman fortress has a superb triumphal arch and temples dedicated to gods such as Mithra – most of which date back to the 3rd century AD.

About the trip

The author travelled with Wild Frontiers which offers an 11-day Algerian Colours group tour taking in Algiers, Oran, Djémila and Constantine in the north as well as mountains and oasis towns in the south. This includes accommodation, all meals, guided excursions and transfers.

Source : https://www.wanderlust.co.uk/content/algeria-empires-of-the-dunes/