For centuries, historians have been mainly interested in the history of men, knowingly ignoring a good half of humanity, and especially the history of women in the Maghreb and more precisely in Algeria. However, by consulting epigraphic documents (inscriptions on stone), we can easily see the position and place that they occupy within the family unit.

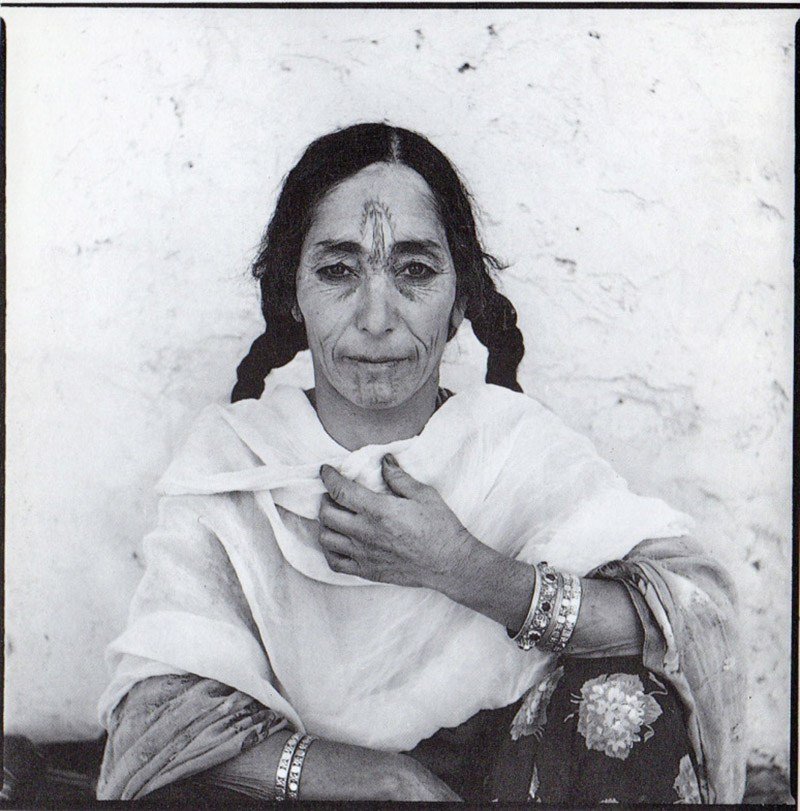

In fact, they reside and dominate as wives, mothers and mistresses of the home from the pre-Roman period. During this period, the woman praised was not the aesthetically pleasing one, but the worker on whom the prosperity of the household depended. The woman who painted her face and body with drawings (natural colouring) was considered to be unchaste and light-hearted, like the women of lesser virtue. Sobriety, purity and work were the values of the ancient Maghrebi woman.

In the Muslim period, the ‘Algerian’ woman had to be protected because she was considered to be the progenitor, destined to perpetuate the group. It was therefore preferable for her to remain in the harem: a private, closed space, inaccessible to foreign males. The veil she wore when she was forced to go out created a mobile ‘haram’ (forbidden) around her face and body, protecting her from covetousness.

The question of the harem (the private sphere of the domestic, and the place where Muslim women live), both in its fantasised representations and in its suggested reality, is an essential point in the entire history of women in Islam. Indeed, the harem and polygyny in general dissociate Muslim societies from Western societies. The Western imagination, and subsequently that of all contemporary societies (including our own today), has long been nourished by this Muslim orient: that of the charming and lascivious odalisque, so far removed from all considerations and concerns of daily life… However, the reality is quite different; the gynecary is even intimately linked to politics and women often had to play important roles as ambassadors, regents, or even as supporters of one faction against another. It was even whispered that 50% of politics was already played within the gynae…

The word harem thus condenses all the fantasies of Europeans. But foreigners do not have access to it, so what they do not know is that the harem is not a place of idleness and debauchery, but the kingdom and prison of unruly women. The women revolt against the coloniser and, at the same time, against their millennial confinement. They understand that the same prohibitions that still weigh on the body and its mere presence, not so long ago, also weighed on the body, the gaze and the voice of European women, and that emancipation requires education.

Thus, during the war of national liberation in Algeria, women fought alongside men and left (sometimes temporarily) the harem and the veil. The war can therefore be seen as a catalyst for the emancipation of women.

As a result, and although it was confined to family life, the outbreak of the war in November 1954 was considered by these women as an ideal opportunity to free themselves from the colonial shackles. As a result, out of the 1010 combatants of the first hour, the 49 women who joined the FLN-ALN in the first month represented 5% of the initial number of combatants. This new situation led the leaders of the insurrection to integrate women into the new equation, this time as a significant variable. This inclusion of women, although difficult at first, was fully accepted.

However, if until the 1980s, Algerians were all subject to the civil code, in 1984, a family code was adopted, behind closed doors, in the APN (Assemblée Populaire Nationale), in which women’s representation was almost non-existent. It is commonly acknowledged, including by some politicians, that the family code is unfair in at least two provisions: polygamy and tutorship. The first deprives women of the right to jealousy and the second makes them minors for life.

However, several feminist associations have been created to fight against this status. Grouped in a women’s coordination, these associations have organised numerous demonstrations to influence the public authorities. The black decade suspended political life in Algeria. The relative return to calm has allowed the debate to be re-launched.

Today, although some amendments are positive, the fact remains that the abolition of this code is quite simply necessary. For the Algerian woman, who has participated in all the crucial periods of her country, must be equal to the man in law. Today, nothing justifies her inferior status. Moreover, her emancipation will only be beneficial for the future of Algeria. Comparative studies, sociological and economic analyses show that where women are inferiorised, society does not progress, or progresses slowly, than those who favour equality between men and women, wrote an Algerian academic in one of his texts.

From the not-so-lascivious odalisque to the courageous and militant woman with evocative slogans of the 1990s, via the bomber with her emblematic haiek of the 1950s, Algerian women continue their struggle and confirm their place, position and status by imposing themselves in more modern times in all sectors of society: economic, legal, political and socio-cultural.

Translated by Hope from https://babzman.com/role-et-statut-social-des-femmes-algeriennes-a-travers-lhistoire/