BYROBERT MAISEY In https://www.jacobinmag.com/

Endgame

On June 19, 1965, the population of free Algiers awoke to the sight of tanks on the streets. For the last several weeks the city had been gearing up to host a high-profile Afro-Asian heads of state conference. Heralded as Bandung 2, the summit would set the tone for the next phase of the world revolution in the Global South. With just days to go, even as foreign dignitaries were arriving, Boumédiène struck out against his erstwhile ally Ben Bella.

The reaction from the population was muted. The coup came as a fait accompli, with Ben Bella abducted from his humble city residence while still asleep. The highly visible military presence on the streets dissuaded any attempt at spontaneous protest.

But what exactly had happened? Despite the exuberance of the Algerian revolution, like all revolutions, it simmered with contradictions just below the surface. Ben Bella’s ambitions to foster genuine popular control of industry had faltered against the demands of state-led modernization. Peasant farmers who had only just begun to exercise genuine autonomy found themselves pushed by demands to implement rapid mechanization of production — and pulled by equally powerful demands to produce large quantities of surplus to plow back into industrial development, particularly in the oil and gas sector.

Further, the cosmopolitanism of the Ben Bella government was increasingly viewed with hostility by conservative elements in Algerian society, including within the FLN coalition itself. Although Ben Bella espoused a brand of revolutionary nationalism that claimed to harmonize the Arab identity with socialism, it was clear enough that the modernism of the regime viewed Islamism as a reactionary force to be suppressed. The foreigners who poured into the country, whether ideological fellow travelers, journalists, or representatives of the fraternal governments, were referred to contemptuously as “pied rouges,” first behind closed doors but later more openly in the conservative sections of the press. Most significantly, nationalism was taking on an increasingly xenophobic character within the ranks of the army.

The scheduled Afro-Asian summit brought these underlying tensions to a climax within the Algerian power system. From Ben Bella’s point of view, the conference would solidify his position as a truly international statesman and allow him to imprint his authority over both the Algerian revolution and his opponents within it. For Boumédiène, Algeria’s de facto second in command, it represented the last moment at which Ben Bella could be challenged before he acquired a Castro-like godhead status.

The same year Ben Bella was toppled, Kwame Nkrumah was removed from office in Ghana, and coups also felled governments in Nigeria, Congo, and several other African nations. Shortly afterward, Nasser was humiliated in the disastrous 1967 war against Israel, announcing foreclosure on the Third World’s most idealistic and pluralistic era.

Although many in the Third World feared that Boumédiène’s military coup represented a dramatic turn toward counterrevolution and Western alignment, this was not, in fact, the case. Socialization of the economy continued, but with the emphasis shifted further toward Soviet-style central planning, oriented around developing the country’s enormous hydrocarbon reserves. On the international field, Algeria remained committed to Non-Alignment, arguing forcefully at the United Nations for a global economic reconfiguration in favor of the developing world. However, even this internationalism took on increasingly statist forms, culminating in Algeria’s participation in the formation of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The OPEC cartel succeeded in crippling the global economy through manipulation of crude oil pricing, inadvertently triggering the wildfire spread of neoliberalism in the suddenly deindustrializing West, but rapidly spreading to the Third World and the communist bloc.

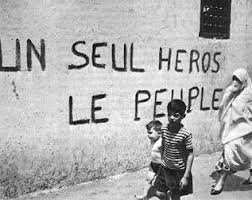

The Algerian revolution was absolutely central to the political landscape of the mid-twentieth century. Within it, the dynamics of decolonization and the Cold War played out in a visible spectacle. Geographically at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, and holding out politically between the communist and capitalist world systems, Algeria’s international status greatly surpassed what anyone expected from a war-torn country with such a small and impoverished population.

Although it has faded away from the global limelight in recent decades, it remains one of the most modern states in the Arab world, both in terms of its infrastructure and culture. Algeria’s struggle has been long and grim, but not less heroic for it.